If you’re trying to decide whether or not to buy a long-term asset for your business (like a vehicle, machine or some expensive software), you want to be reasonably assured that it will be worth it. By “worth it”, we mean that the benefits outweigh the costs. Capital budgeting helps evaluate the whether a long-term asset will pay off.

If you’re trying to decide whether or not to buy a long-term asset for your business (like a vehicle, machine or some expensive software), you want to be reasonably assured that it will be worth it. By “worth it”, we mean that the benefits outweigh the costs. Capital budgeting helps evaluate the whether a long-term asset will pay off.

This article won’t make you an expert in capital budgeting. It should however, provide you with a good overall understanding of capital budgeting and some commonly used techniques. To get the most of this article, it’s best to have an understanding of the time value of money.

To help make that “to buy or not to buy” decision, we introduce four common approaches to capital budgeting:

-

Payback Period

-

Accounting rate of return

-

Internal rate of return

-

Net present value

Example Company – Frodo’s Bakery

The easiest way to understand the approaches to capital budgeting is take a look at them using an example company. We’ll use the example of a fictitious bakery called Frodo’s Bakery (let’s say Frodo found that the market for rings and other jewelry was saturated, so he opened a bakery instead).

Frodo’s Bakery is thinking about buying a new automatic bread cooker that would cost $70,000 and last 5 years. It would boost capacity and decrease operating costs, allowing Frodo to increase profits by $20,000 per year. Frodo’s cost of capital is 10% (or, Frodo’s interest rate is 10%). Frodo expects the cooker to have a $10,000 salvage value (in other words, Frodo expects to sell the cooker for $10,000 at the end of 5 years). Is the investment in the new cooker worthwhile?

Payback Period Method

The payback period calculates the number of periods needed to recover a project’s initial investment ($70,000 in this case). Since Frodo gains $20,000 per year from the investment, the payback period is 3.5 years (3.5 x $20,000 = $70,000).

Many people consider the payback period to be a measure of risk. The longer the payback period for the investment, the higher the risk.

There are two main problems with the payback period capital budgeting approach:

-

The payback period method ignores the time value of money. We know that because of the time value of money, it is always better to receive money earlier than later. Cash received earlier should be weighted differently than cash received later.

-

It ignores cash outflows that happen after the initial investment and the cash inflows that occur after the payback period. For example, say that Frodo could have bought a different bread cooker which provides the same cash flows as cooker 1 except that it has a disposal value of $20,000. Of course, it’s better for Frodo to buy the cooker he can sell after 5 years for $20,000 but the payback method would consider both choices to be equivalent because the their payback periods are the same at 3.5 years.

Despite these limitations, the payback period approach is one of the most widely used. Probably because of its simplicity.

Accounting Rate of Return Method

The accounting rate of return approximates the return on an investment. It’s calculated by dividing the average accounting income from the investment by the average level of investment.

Accounting Rate of Return = Average Income / Average Investment

Suppose Frodo decides to depreciate the cooker using the straight-line method (meaning that the value of the cooker decreases by the same amount each year). With a $10,000 salvage value, this means that the cooker will decrease in value by $12,000 per year for the 5 years.

Annual depreciation = (Historical Cost – Salvage Value) ÷ Asset Life = ($70,000 – $10,000) ÷ 5 = $12,000.

Therefore, the increased income Frodo will report thanks to the new cooker will be $8,000 ($20,000 – 12,000).

The average investment for the cooker will be $40,000 as shown below:

Average investment = (Initial investment + Salvage Value) ÷ 2 = ( $70,000 + $10,000 ) ÷ 2 = $40,000

This means the accounting rate of return for the cooker will be:

Accounting Rate of Return = Average Income ÷ Average Investment = $8,000 ÷ $40,000 = 20%

If the 20% accounting rate of return is greater than the target rate of return, Frodo should by the cooker.

The accounting rate of return method is an improvement of the payback method because it considers cash flows in all periods. However like the payback method, this method has drawbacks because by averaging, the explicit timing of cash flows isn’t considered.

Net Present Value Method

The net present value (NPV) is the sum of all present values of all cash inflows and outflows associated with a project (or investment). This method incorporates the time value of money. To calculate an investment’s net present value, we can use the following six steps:

-

Choose the appropriate length of time to evaluate the investment proposal. The most common period length used in practice is annual, although some analysts also use quarterly or semiannual period lengths. In the example case of Frodo’ bakery, use 1 year because all cash flows are stated annually.

-

Identify the company’s cost of capital for the period length chosen in step 1. Frodo’s stated cost of capital is 10% per year. Since the period chosen in step 1 is annual, no adjustment to the 10% is necessary.

-

Identify the incremental cash flow in each period of the project’s life. In Frodo’s case, there is an immediate $70,000 cash outflow to pay for the cooker and $20,000 cash inflow at the end of each year for 5 years. Finally, a $10,000 cash inflow (salvaged) at the end of 5 years. It’s best to organize the cash flows associated with a project on a time line like the one shown. This allows you to identify and consider all the project’s cash flows systematically.

-

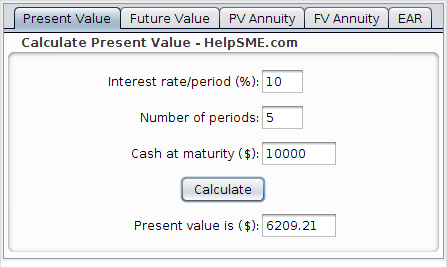

Calculate the present value of each period’s cash flow. In Frodo’s case, we have a five-year annuity of $20,000 at 10% and a $10,000 cash inflow in 5 years as the salvage value.

We can use our financial calculator to show that the present value of the annuity is $75,816.

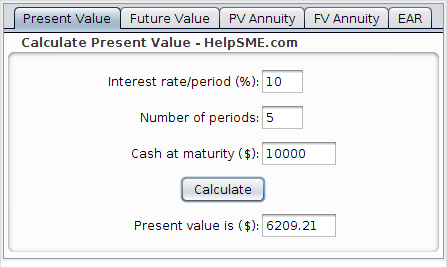

The present value of the $10,000 salvage in 5 years when Frodo’s cost of capital is 10% is $6209.

-

Add up the present values of all the periodic cash inflows and outflows to determine the investment’s net present value. In the case of Frodo’s Bakery, the present value of cash inflows from the investment is $82,025 ($75,816 + $6209). Because the $70,000 investment happens at time zero (immediately), its net present value of that cash outflow is $70,000. This gives us a net present value for this investment of $12,025 ($82,025 – $70,000).

-

If the project’s net present value (also called residual income) of a project is found to be positive, the project should be accepted from an economic perspective. In the case of Frodo’s Bakery, it would be worthwhile to buy the new cooker because the net present value is positive ($12,025).

Internal Rate of Return Method

The internal rate of return (or IRR) is the rate of return expected from a project or investment. It is the discount rate that makes the net present value of the project equal to zero. If an investment’s net present value is positive, it means that it’s IRR is greater than its cost of capital. In other words, the project’s rate of return exceeds the rate to fund the project.

We can use trial and error to find the IRR for Frodo’s cooker. We substitute various values for the rate of return in our net present value calculation. The value that yields a net present value of zero is 16.14%. Because the IRR for the investment is greater than the 10% cost of capital, the project is desirable.

A project’s net present value summarizes all of its financial elements. This means you don’t need to use the IRR method to prepare financial budgets. Moreover, the IRR method has disadvantages:

-

It assumes a company can reinvest a project’s intermediate cash flows at the project’s internal rate of return. This assumption is often invalid.

-

Using the IRR method to evaluate proposed investments can produce ambiguous results, especially when evaluating competing projects when the company doesn’t have enough cash available to invest in all positive net present value projects.

The net present value calculation is superior to the IRR method and only requires one extra piece of information for the calculation – the company’s cost of capital. Nevertheless, internal rate of return is pervasive in financial markets and is widely used in capital budgeting.

The Effect of Taxes

So far, we’ve ignored the effect of taxes in our capital budgeting calculations. In practice, the effect of taxes needs to be taken into account. Tax laws vary from region to region but in general, taxes have two major effects:

-

Companies have to pay taxes on the net cash benefits resulting from an investment.

-

Companies can use the depreciation cost of a capital investment to offset some of the tax burden.

Tax rates and the methods companies are allowed to use to depreciate acquisition costs of their long-term assets vary. Nevertheless, the concept is usually the same – taxes are paid on income from the investment while depreciation expense from that investment reduces taxes paid.

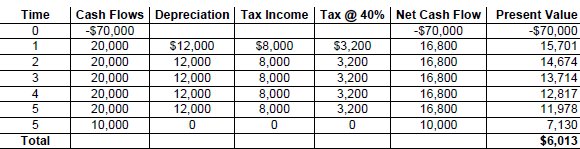

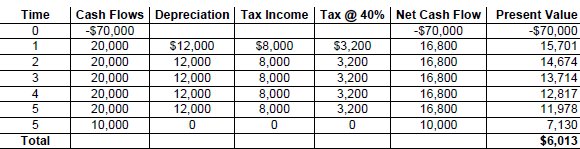

To continue with our example, let’s assume Frodo’s bakery is taxed at a rate of 40% and has an after-tax cost of capital of 7%. To convert all pretax cash flows to after-tax cash flows, we need to know the amount of depreciation that will be claimed each year. Using straight-line depreciation, Frodo will claim $12,000 depreciation each year, as mentioned earlier.

We can now compute the after-tax cash flows resulting from this investment:

Net Present Value Calculation With Taxes

As we can see, the project’s net present value is positive ($6,013) which means the investment is desirable.

If your business is on solid ground and you’re looking to expand, you’ll need to finance that growth. Expansion can involve a lot more than growing your customer base. It can mean tackling new markets, buying more equipment, offering new products, hiring employees and more. All of this requires money. But where can you find the required financing?

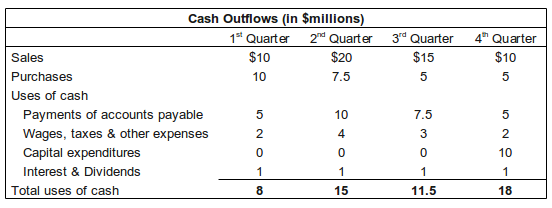

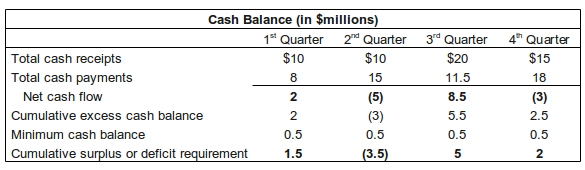

If your business is on solid ground and you’re looking to expand, you’ll need to finance that growth. Expansion can involve a lot more than growing your customer base. It can mean tackling new markets, buying more equipment, offering new products, hiring employees and more. All of this requires money. But where can you find the required financing? The cash budget is an essential tool for

The cash budget is an essential tool for

If you’re trying to decide whether or not to buy a long-term asset for your business (like a vehicle, machine or some expensive software), you want to be reasonably assured that it will be worth it. By “worth it”, we mean that the benefits outweigh the costs. Capital budgeting helps evaluate the whether a long-term asset will pay off.

If you’re trying to decide whether or not to buy a long-term asset for your business (like a vehicle, machine or some expensive software), you want to be reasonably assured that it will be worth it. By “worth it”, we mean that the benefits outweigh the costs. Capital budgeting helps evaluate the whether a long-term asset will pay off.

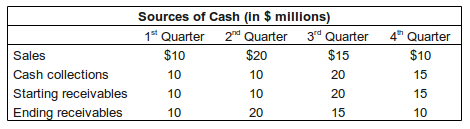

When a company makes a sale, it can either collect payment right away in cash, or extend credit to the customer and collect payment later.

When a company makes a sale, it can either collect payment right away in cash, or extend credit to the customer and collect payment later. Most companies hold some of their assets in cash – even though cash earns no interest. Why hold cash instead of investing it in promising projects or short-term securities? Of course, one reason for holding cash is to pay for goods, services and wages. A company might prefer to pay its employees with short-term government bonds but that simply wouldn’t be practical. The main reason for holding cash is to facilitate the payments and collections for the regular activities of the firm. Cash inflows (collections) and outflows (payments) are not perfectly synchronized. Some cash holdings are necessary as a buffer.

Most companies hold some of their assets in cash – even though cash earns no interest. Why hold cash instead of investing it in promising projects or short-term securities? Of course, one reason for holding cash is to pay for goods, services and wages. A company might prefer to pay its employees with short-term government bonds but that simply wouldn’t be practical. The main reason for holding cash is to facilitate the payments and collections for the regular activities of the firm. Cash inflows (collections) and outflows (payments) are not perfectly synchronized. Some cash holdings are necessary as a buffer. Smaller startups are often less concerned with long-term planning than getting off the ground and surviving. While many businesses may benefit from long-term financial planning, the more established businesses tend to have the resources and stability to analyze the long-term.

Smaller startups are often less concerned with long-term planning than getting off the ground and surviving. While many businesses may benefit from long-term financial planning, the more established businesses tend to have the resources and stability to analyze the long-term. Short-term financial planning is important for virtually all businesses – from small startups to large established businesses. Even large businesses with seemingly healthy

Short-term financial planning is important for virtually all businesses – from small startups to large established businesses. Even large businesses with seemingly healthy  One of the most important concepts in corporate finance is the time value of money. This concept is crucial in areas like

One of the most important concepts in corporate finance is the time value of money. This concept is crucial in areas like